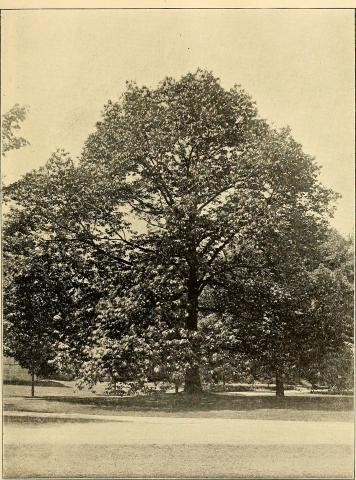

One in four hardwood trees in the eastern United States was once an American chestnut. But no one today can take a walk in these woods beneath the once towering chestnut trees because the species is functionally extinct.

First spotted in the Bronx Zoo in 1904, Cryphonectria parasitica (commonly known as chestnut blight) is a fungus that parasitizes the American chestnut. Thought to have been brought to the United States from Asia, it grows on and beneath the bark, releasing an acid that kills the tree. The blight spread across the country at a rate of roughly 50 miles per year. It was spread, in part, by loggers carrying the fungus on their shoes and axes. Communities in Pennsylvania burned infected trees to no avail – by 1940 most adult American chestnut trees were dead.

The decimation of the chestnut is among the worst ecological disaster in the world’s forests in history. But now, genetic engineering and conservation are being brought together to save a species, for the first time.

The American chestnut was integral to life in the eastern US. Chestnuts were a source of food and medicines for the Cherokee, and were culturally important to the Iroquois. When white settlers expelled Indigenous peoples and occupied the land, they relied on the tree for food, lumber and often their livelihoods. Its lumber was remarkably useful for building. Described as a tree that “carried man cradle to grave in crib and coffin,” it was soft and easy to work while being rot-resistant. Tannic acid from the tree fueled 21 tanneries in the Appalachians. Chestnuts were used to feed livestock – for several months of the year, hogs would roam the woods, eating nuts that coated the forest floor. Many species that people hunted as game ate chestnuts as a dominant food source. The loss of the American chestnut threw ecosystems off balance and led to the extinction of at least seven moth species that called the trees home.

Using the naturally blight-resistant Chinese chestnut, the USDA started a program in 1922 to breed for blight resistance. Initially thought to be linked to one or two genes, resistance is now understood to be much more complicated, potentially involving nine of the 12 chestnut chromosomes. This complication makes the task of full-scale resistance via breeding daunting. Breeding can also lead to negative traits such as male sterility and traits that are phenotypically more Chinese chestnut than American chestnut.